When I first started doing web development, it was primarily with Python/Django. Everything was server side rendered and not once did I ever think about “rendering performance”. 10 years later and with computers at least twice as fast, rendering performance is now more of an issue than it ever has been. Single Page Apps (SPAs) and frontend libraries like React have encouraged and enabled highly dynamic web pages. Unfortunately, in my experience, the default recommended way to write React code does not actually support highly dynamic pages very well.

In this post I will explore the problems that come with standard React code, the recommended options for improving React performance, and finally counter these with examples in vanilla JS.

What We’re Building

Coming up with a succinct example is difficult as it is really the complexities of a real project that better demonstrate how everything comes together. This post will walk through a basic “dynamic” example that highlights how React performs when state is frequently changing. The example is 500 text divs that have their background color updated when one of the elements is hovered over. After each set of changes I will include the source code and screenshots of the profiler to show how much time React is spending rendering.

Initialize project using Create React App

The initial base of this code is from the create-react-app typescript template. I’ve only modified the App.tsx file across my examples to make it easier to see all changes at once.

npx create-react-app react-overreact --template typescript

Naive React Solution

In this first example, we will capture the current hovered element as state and use this to update the background color of the element. Before you raise your pitchforks and say that this could simply be done with a CSS :hover, imagine that this hover state is needed for something else and we are just using the backgroundColor property as a way to visualize the state change.

See the code below for what this looks like.

// App.tsx

import React, { useState } from "react";

import "./App.css";

function App() {

const [hoveredElementId, setHoveredElementId] = useState("");

const elements = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 500; i++) {

const elementId = String(i);

const isHovered = hoveredElementId === elementId;

elements.push(

<div

key={i}

style={ { marginBottom: 8, backgroundColor: isHovered ? "#eee" : "" } }

onMouseEnter={() => {

setHoveredElementId(elementId);

}}

onMouseLeave={()=> {

if (elementId == hoveredElementId) {

setHoveredElementId("");

}

}}

>

div

</div>

);

}

return <>{elements}</>;

}

export default App;

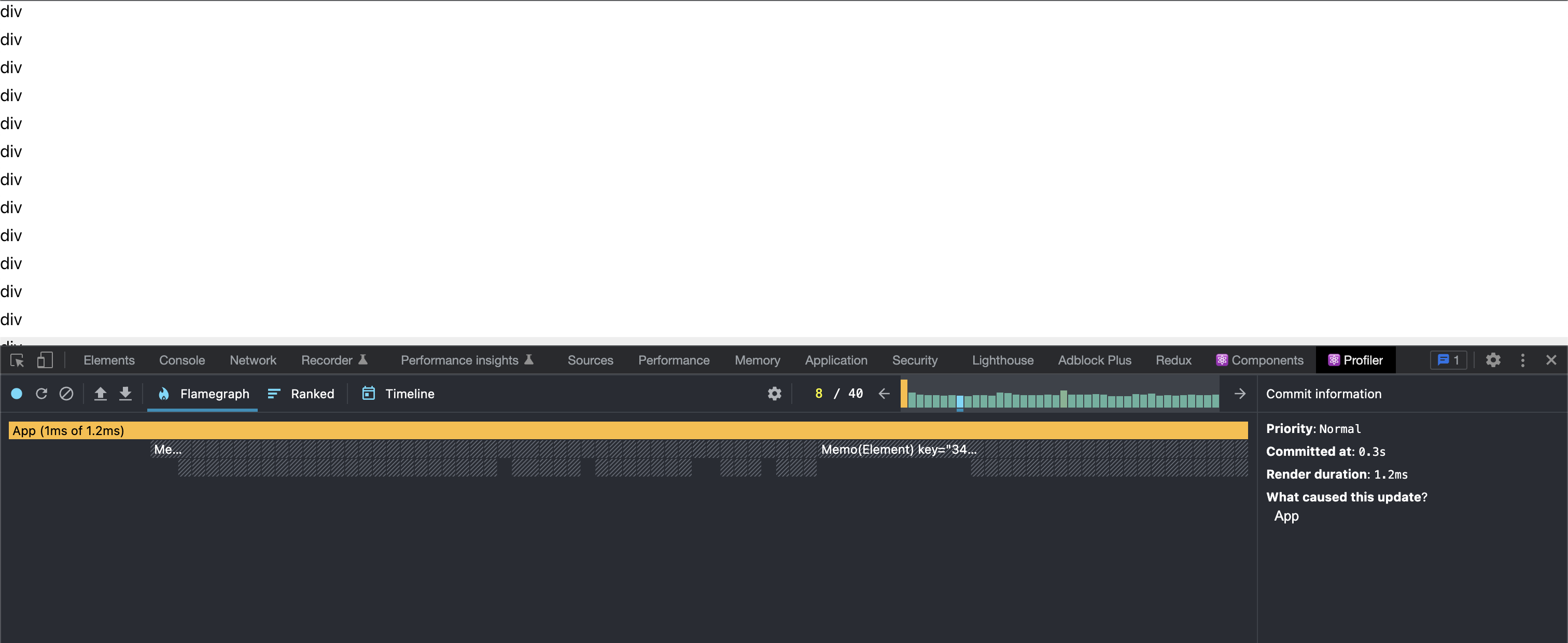

Profiler

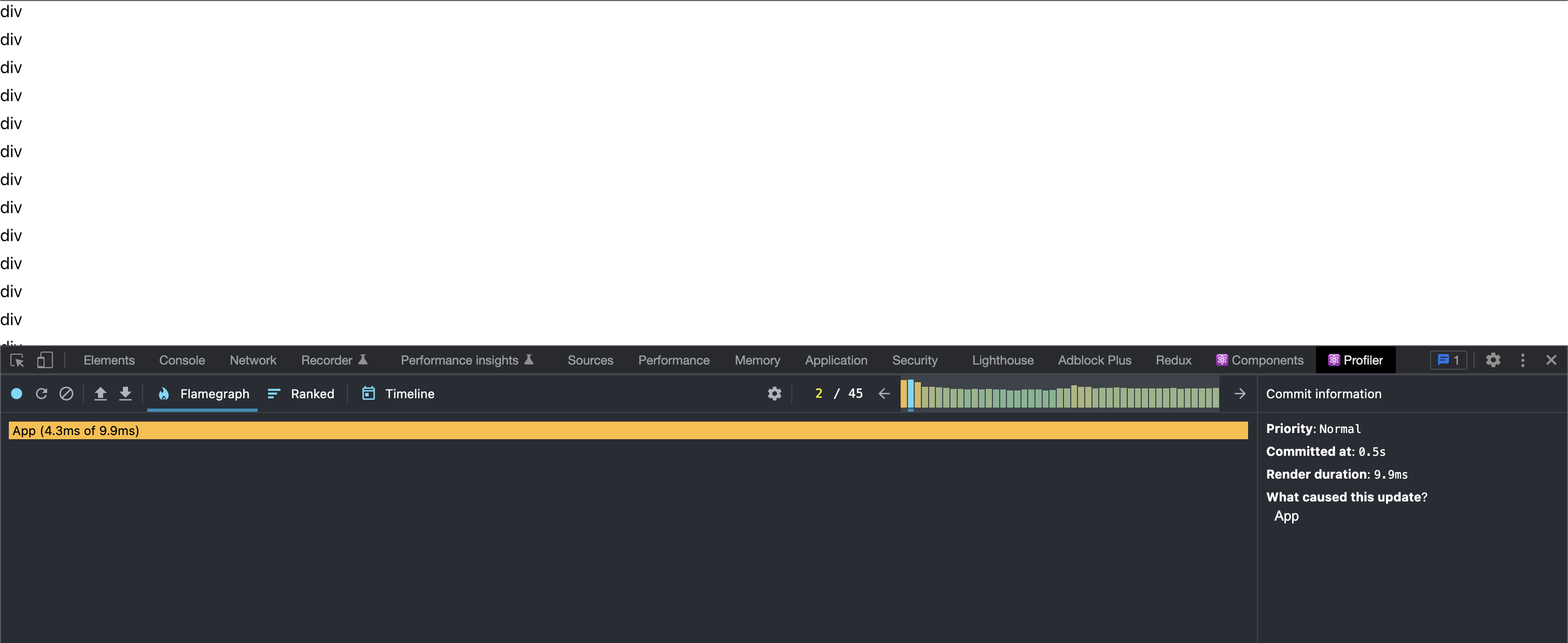

On an M1 Macbook Pro a single render clocks in at between 3ms and 9ms. You can also see that every time a new element is hovered a new render is triggered. If you’re thinking under 10ms sounds pretty fast, please remember that the M1 chip is one of the fastest single threaded performing CPUs currently available. It’s easy to imagine that there would be older devices that could be at least twice as slow. This is also all with the simplest text element. Even just a few more elements inside the repeated element would start tacking on additional milliseconds of rendering time.

I would like to acknowledge that there should be “some” overhead from using the development build, but I wouldn’t expect turning on production mode would have a substantial impact on this example.

Update:

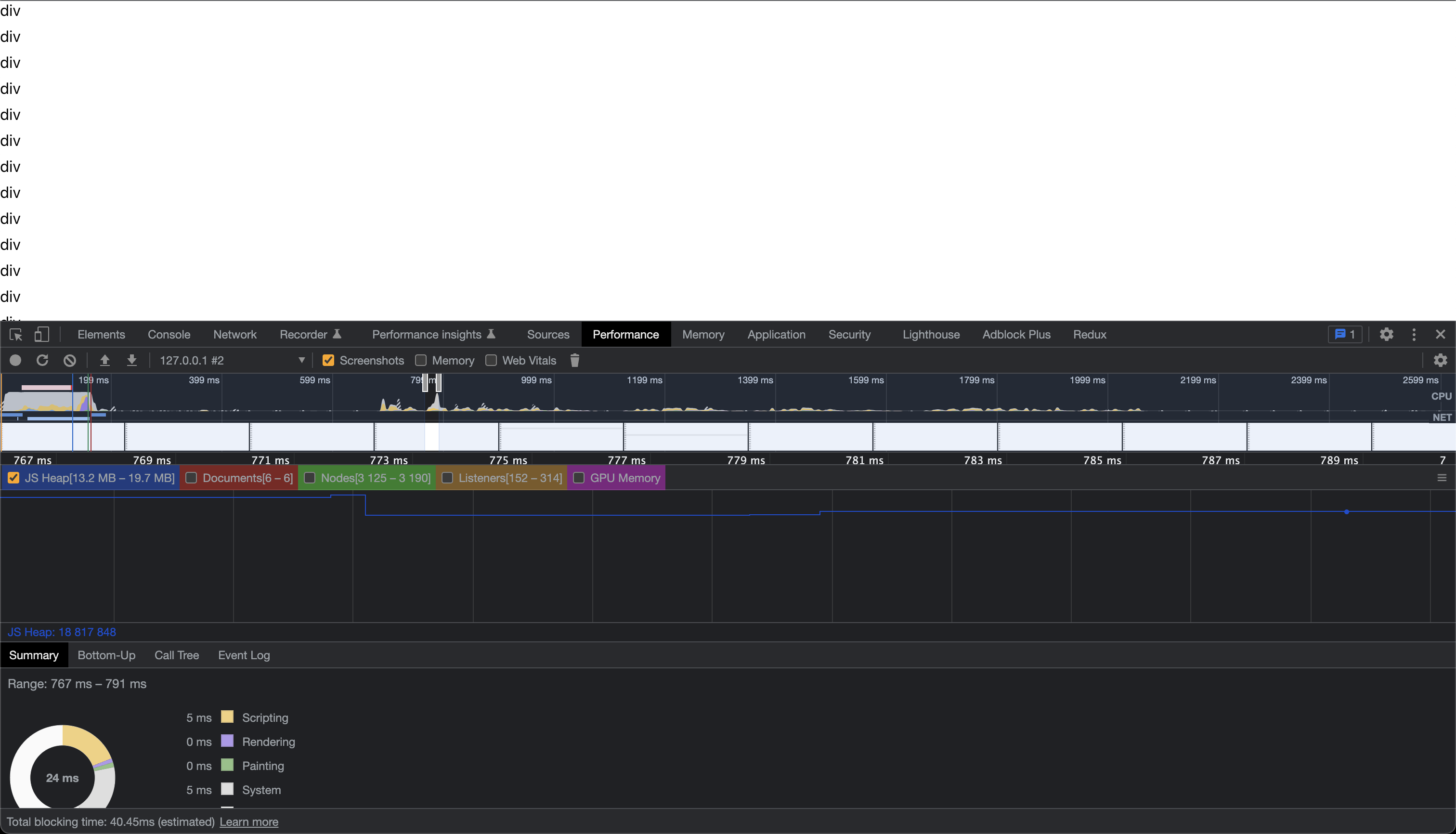

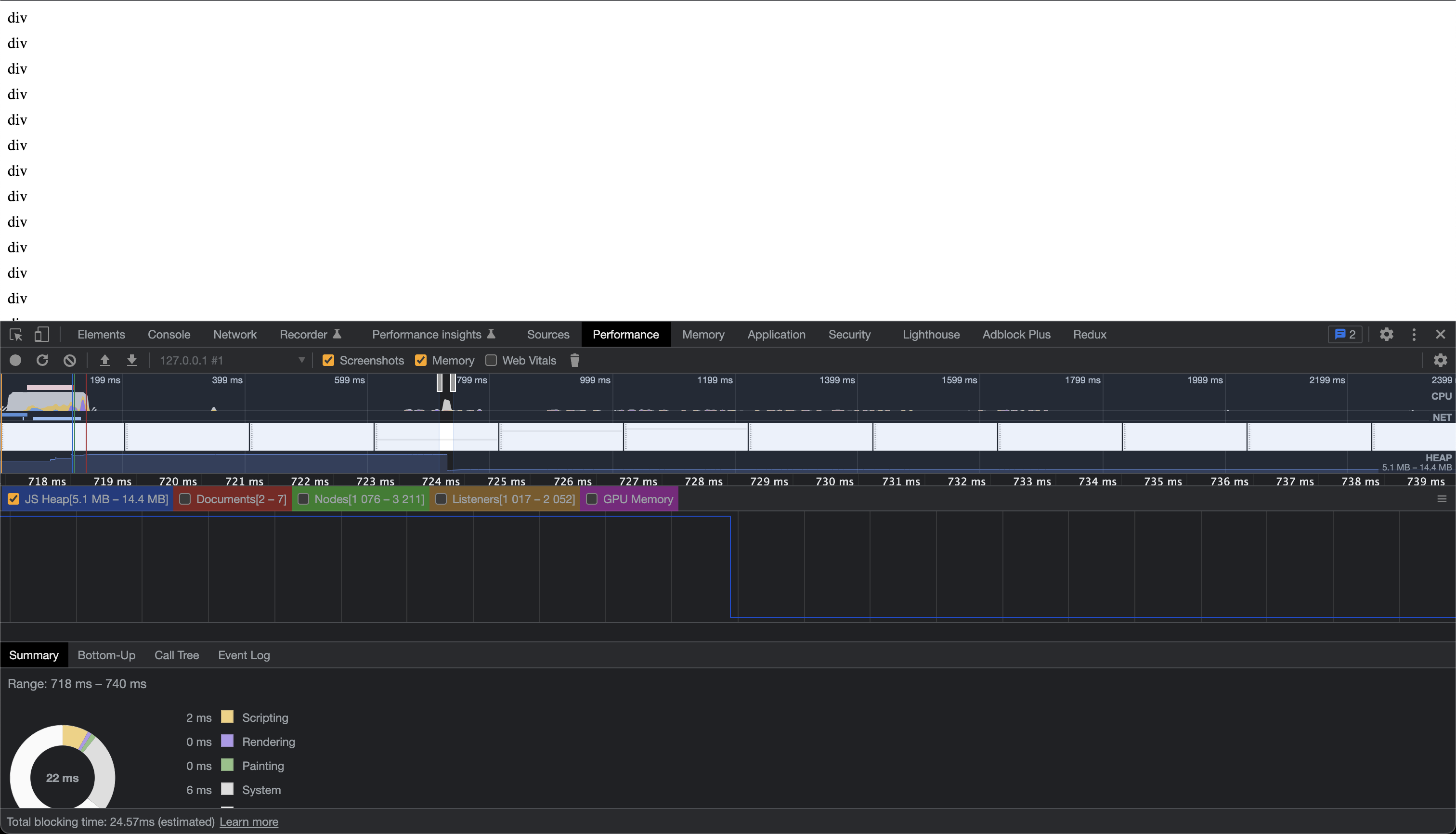

I tried a few different methods to profile in production, but each came to the same conclusion. The fairest apples to apples comparison to my final example at the end of this article is a full production build (yarn build) and the Chrome Performance tab.

Chrome Performance Tab

Below you can see that the numbers without any additional React development overhead look quite similar to what the React Dev Tools are showing.

I come from a game development background where it is ingrained in you that your frame needs to complete all processing in under 16ms in order to maintain 60 frames per second. With just 500 elements I have nearly passed this threshold already with React. Once a frame takes more than 16ms, the stutter becomes noticeable and renders get queued up leading to a horrendous user experience.

Optimizing Performance in React

On React’s Optimizing Performance page, they claim “For many applications, using React will lead to a fast user interface without doing much work to specifically optimize for performance.” In my opinion, this should be re-worded as “most applications won’t have enough elements to worry about React’s default excessive rendering”.

One of the first suggestions in this list is Virtualize Long Lists. Per their docs: “If your application renders long lists of data (hundreds or thousands of rows), we recommend using a technique known as “windowing””. This makes sense in the realm of an infinite list, but in the low 100s of elements, this is an unnecessary complication to add on top of things. In the real world example I was working with that led to this article there were highly nested components, which means that sometimes a single element was quite simple, and other times a single element could have several other components. Windowing with this would require computing the dynamic height of every single element probably leading to even worse performance than just showing all of the elements in the first place.

The next example suggests Avoid Reconciliation. Essentially suggesting to update the component so that if the props haven’t changed the component doesn’t re-render. When I first learned this I had to do a double take. I thought the entire point of React was that if the props didn’t change then there’s no work to be done in a component. But it turns out React just blindly re-renders the entire subtree if a prop of a parent changes.

Remember that helpful page that suggested this? Well none of it actually tells you how to do this with functional components. The only page on the react website devoted to Performance Optimizations doesn’t bother to give you any information about how to optimize using hooks (which is now the recommended way of using React). Instead, details about hook optimizations is buried in the Hooks FAQs for you to find once it’s too late.

Avoid Reconcilation with React.memo (or not)

import React, { useState } from "react";

import "./App.css";

type ElementProps = {

id: string;

hoveredElementId: string;

onMouseEnter: (id: string) => void;

onMouseLeave: (id: string) => void;

};

function Div(props: ElementProps) {

const isHovered = props.hoveredElementId === props.id;

return (

<div

style={ { marginBottom: 8, backgroundColor: isHovered ? "#eee" : "" } }

onMouseEnter={() => {

props.onMouseEnter(props.id);

}}

onMouseLeave={() => {

props.onMouseLeave(props.id);

}}

>

div

</div>

);

}

function App() {

const [hoveredElementId, setHoveredElementId] = useState("");

const handleMouseEnter = (id: string) => {

setHoveredElementId(id);

};

const handleMouseLeave = (id: string) => {

if (id == hoveredElementId) {

setHoveredElementId("");

}

};

const elements = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 500; i++) {

elements.push(

<Div

key={i}

id={String(i)}

hoveredElementId={hoveredElementId}

onMouseEnter={handleMouseEnter}

onMouseLeave={handleMouseLeave}

/>

);

}

return <>{elements}</>;

}

export default App;

First we pull the inner element into it’s own React component in order to benefit from the ability to prevent re-renders. Functionally this should be pretty much the same as the first code block we started with. The profiler shows us we’re now at 4ms - 16ms. That last number should look familiar…we’re already teetering into dipping below 60fps just from introducing a React component to wrap our basic div (you can use your imagination to picture what happens when that inner component has multiple children of its own).

Profiler

The code above still triggers a full render every time the hovered element id changes. This is because we are passing in the hoveredElementId to the element and therefore each child’s props are changing every time the hovered element changes triggering full re-renders for everything.

Use React.memo with propsAreEqual callback

An element only needs to re-render if the hoveredElementId is the current element (in which case we need to update the backgroundColor), or the previous hoveredElementId matches the current element (in which case we need to remove the backgroundColor style).

In the code below, we check whether the prevProps.hoveredElementId or nextProps.hoveredElementId match the id of our element. If it does, we return false to indicate that the component should be re-rendered. We also need to make sure that changes to other props trigger a re-render as so we make sure to perform and equality check on the rest of the properties using lodash’s isEqual. By default, React.memo does a shallow compare, but as far as I can tell, they don’t actually expose a convenient function for you to use to do your own shallow compare.

import _ from "lodash";

import React, { useState } from "react";

import "./App.css";

type ElementProps = {

id: string;

hoveredElementId: string;

onMouseEnter: (id: string) => void;

onMouseLeave: (id: string) => void;

};

function Element(props: ElementProps) {

const isHovered = props.hoveredElementId === props.id;

return (

<div

style={ { marginBottom: 8, backgroundColor: isHovered ? "#eee" : "" } }

onMouseEnter={() => {

props.onMouseEnter(props.id);

}}

onMouseLeave={() => {

props.onMouseLeave(props.id);

}}

>

div

</div>

);

}

const MemoedElement = React.memo(Element, (prevProps, nextProps) => {

const { hoveredElementId: oldHoveredElementId, ...oldProps } = prevProps;

const { hoveredElementId: newHoveredElementId, ...newProps } = nextProps;

if (oldHoveredElementId === nextProps.id) {

return false;

}

if (newHoveredElementId === nextProps.id) {

return false;

}

return _.isEqual(oldProps, newProps);

});

function App() {

const [hoveredElementId, setHoveredElementId] = useState("");

const handleMouseEnter = (id: string) => {

setHoveredElementId(id);

};

const handleMouseLeave = (id: string) => {

if (id === hoveredElementId) {

setHoveredElementId("");

}

};

const elements = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 500; i++) {

elements.push(

<MemoedElement

key={i}

id={String(i)}

hoveredElementId={hoveredElementId}

onMouseEnter={handleMouseEnter}

onMouseLeave={handleMouseLeave}

/>

);

}

return <>{elements}</>;

}

export default App;

Profiler

Unfortunately, this first attempt fails. The reason for this is incredibly non-obvious. When the hoveredElementId state changes it triggers a re-render of the App component. I still have a very poor mental model of what React is actually doing behind the scenes, but essentially handleMouseEnter and handleMouseLeave get redefined on each render. Which means when they get passed back in to MemoedElement they are no longer the same reference, which causes the MemoedElement to fully re-render itself again.

useCallback to Prevent Callbacks from Triggering Unnecessary Renders

Another dive through the Hooks FAQ leads us to “Are hooks slow because of creating functions in render”.

| Traditionally, performance concerns around inline functions in React have been related to how passing new callbacks on each render breaks shouldComponentUpdate optimizations in child components |

Here React admits to the fact that callbacks in functional components are broken by default. In the code below I updated my callbacks to be wrapped with the magical useCallback.

import _ from "lodash";

import React, { useCallback, useState } from "react";

import "./App.css";

type ElementProps = {

id: string;

hoveredElementId: string;

onMouseEnter: (id: string) => void;

onMouseLeave: (id: string) => void;

};

function Element(props: ElementProps) {

const isHovered = props.hoveredElementId === props.id;

return (

<div

style={ { marginBottom: 8, backgroundColor: isHovered ? "#eee" : "" } }

onMouseEnter={() => {

props.onMouseEnter(props.id);

}}

onMouseLeave={() => {

props.onMouseLeave(props.id);

}}

>

div

</div>

);

}

const MemoedElement = React.memo(Element, (prevProps, nextProps) => {

const { hoveredElementId: oldHoveredElementId, ...oldProps } = prevProps;

const { hoveredElementId: newHoveredElementId, ...newProps } = nextProps;

if (oldHoveredElementId === nextProps.id) {

return false;

}

if (newHoveredElementId === nextProps.id) {

return false;

}

return _.isEqual(oldProps, newProps);

});

function App() {

const [hoveredElementId, setHoveredElementId] = useState("");

const handleMouseEnter = useCallback((id: string) => {

setHoveredElementId(id);

}, [setHoveredElementId]);

const handleMouseLeave = useCallback((id: string) => {

if (id === hoveredElementId) {

setHoveredElementId("");

}

}, [setHoveredElementId]);

const elements = [];

for (let i = 0; i < 500; i++) {

elements.push(

<MemoedElement

key={i}

id={String(i)}

hoveredElementId={hoveredElementId}

onMouseEnter={handleMouseEnter}

onMouseLeave={handleMouseLeave}

/>

);

}

return <>{elements}</>;

}

export default App;

Profiler

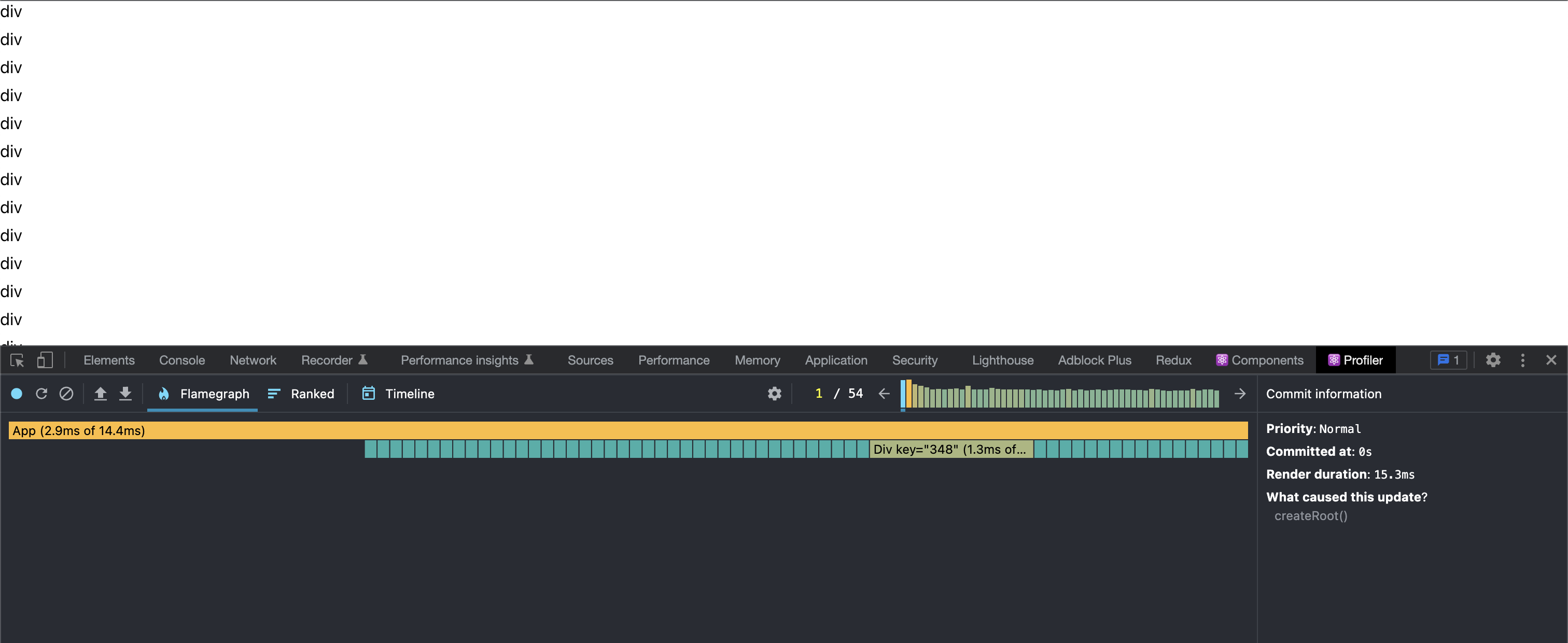

You can see in the profiler screenshot that this has successfully accomplished the goal of not re-rendering every component on every new hover.

In order for this to work, any callback that exists must be wrapped in this useCallback. Don’t dare to miss something in that dependency array or you’ll find yourself with some weird behaviour.

const handleMouseEnter = useCallback((id: string) => {

setHoveredElementId(id);

}, [setHoveredElementId]);

It’s commonly said that “Premature Optimization is the Root of All Evil” in programming. This is often true and the suggested approach is to profile and specifically target problem areas only if they present themselves as problems.

This should hold true as well for writing React code, but the process of optimizing after the fact in React is unenjoyable at best. By the time you know that performance is a problem, you have several different components that all need to be individually memoized. Once you’ve done this you need to seek out all instances where callbacks are giving you grief.

The final code is still somewhat reasonable to follow (if you are aware of these patterns and issues), but the subtleties of dependency arrays and arePropsEqual make it easy to introduce new problems. Adding “just one more thing”, can easily break memoization bringing you back to where you started with terrible performance.

The FAQ next suggests useReducer to avoid having to pass callbacks around multiple components. I won’t go over what this would look like in this article (though you may see a future one that does).

Do We Even Need React?

In the span of this article I have introduced at least 3 separate major React concepts (React.memo, arePropsEqual, and useCallback) in order to get performance that arguably should be default behaviour (and quite frankly, 1ms is still pretty embarassing for 500 elements). I have long questioned what benefits React is actually giving me, and these frustrations I have experienced in the realm of performance are extremely disappointing.

In a future article, I’d like to explore and share some experiments I have been putting together to get myself out of React. But as a teaser, below is code for a similar example in plain old JavaScript.

const root = document.createElement("div");

document.body.appendChild(root);

for (let i = 0; i < 500; i++) {

const element = document.createElement('div');

element.style.marginBottom = "8px";

element.innerText = "div";

element.addEventListener("mouseenter", () => {

element.style.backgroundColor = "#eee"

});

element.addEventListener("mouseleave", () => {

element.style.backgroundColor = ""

});

root.appendChild(element);

}

Profiler

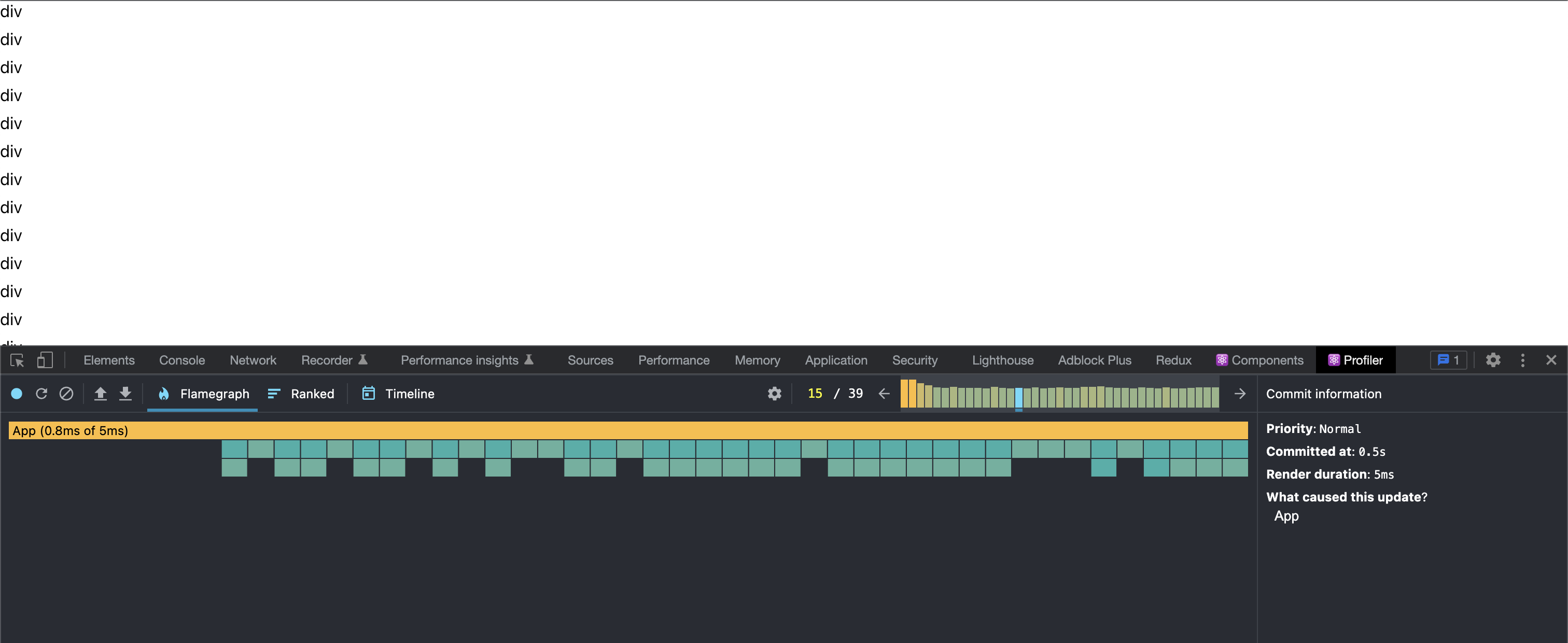

The React Profiler can no longer be used, but the Chrome Performance tab shows that the worst frame was 2ms of Scripting. All the other ones come out as 0ms.

Conclusion

React supporters will claim that this is an unfair representation and that React’s benefits kick in as your project grows larger. In time, I will share how the simple code presented above can be used to sustain large projects without a problem.

Instead of having to learn React’s convoluted ways of working around its component lifecycle, you can instead learn to manage this yourself. I have been doing this for the last several months on my own projects and I don’t think I’ll be turning back.